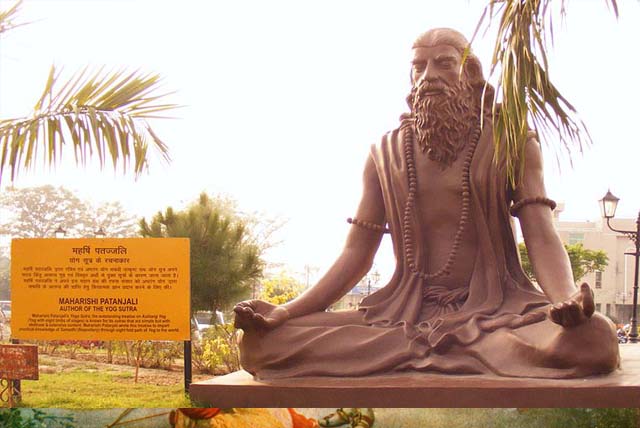

Patanjalis Eight-Limbed Path of Yoga: Yamas

The Eight Limbs are included in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, the classical text on yoga which, while not exhaustive, is accepted as the central guide by all schools of yoga. He defines yoga as “stilling the thought waves of the mind”, a journey from mental distraction, scattered thinking and conceptualising about ourselves, the past and the future to a non-conceptual meditative state of calm and quiet understanding. Patanjali systematised yoga practice into an eight-limbed, or staged, path where all the limbs are inextricably linked.

YAMA (attitude) and NIYAMA (quality) are the framework upon which ASANA (posture) and PRANAYAMA (breathing) are founded effectively leading to PRATYAHARA (meditative-internalisation) and progressing to DHARANA (meditative-concentration), DHYANA (meditative-contemplation) and ultimately to SAMADHI (meditative-absorption).

- YAMAS

Ahimsa

Satya

Asteya

Brahmacharya

Aparigraha

- NIYAMAS

Saucha

Santosha

Tapas

Svadyaya

Ishvara Pranidhana

3. ASANA

4. PRANAYAMA

5. PRATYAHARA

6. DHARANA

7. DHYANA

8. SAMADHI

The Yamas and Niyamas can be considered common-sense guidelines for leading a healthier, happier life in which we bring spiritual awareness into a social context; they are not externally imposed rules, but guides to be contemplated. The Yamas and Niyamas deal with our attitude and lifestyle, the quality of our interaction with other people and the environment, and how we deal with our problems. They cannot be “practised” as such like asanas or pranayama. We can only be aware of our behaviour and then introduce changes in the way we relate to our world. Nobody can change in a day, but yoga practice can help change attitudes and qualities (Yamas and Niyamas), not the other way around. As T.K.V. Desikachar says, “yoga is not a recipe for less suffering, but it can help us in changing our attitude so that we have less avidya (false understanding) and therefore greater freedom from duhkha (pain).”

Yamas and Niyamas are an experiment in conscious living and cause and effect as opposed to commandments. When we try to live like this we can test how we feel and how the world responds to us. We can test if freedom is just doing what we want or if, ironically, it lies in some element of self-discipline. With time, the cultivation of Yamas and Niyamas becomes a source of richness in our daily living and ultimately allows us to live more fully and be more awake.

YAMAS – Universal Laws of Life

They are guidelines to interact with the OUTER WORLD, social disciplines to guide us in our interactions with others. We can apply these to everything, from our diet to our relationships in order to cultivate a harmonious life style which will facilitate our own spiritual journey. There are five Yamas:

Ahimsa: Peaceful Action, Non-violence

Ahimsa stands for non-violence and its positive expression of love and openness. It refers to non-violence in action, thought, or words to other living beings, or towards ourselves. Ahimsa means more than just lack of violence, it means kindness, friendliness, and consideration of other people and things. And of course, viewing ourselves with tenderness and compassion. One aspect of non-violence is creating healthy boundaries; becoming a doormat is not Ahimsa!

Ahimsa in Your Asana Practice:

Aggression in asana manifests as the energy of trying to push into a shape that seems unavailable at any particular instance. Letting go of aggressive pushing towards the “ultimate” form of a posture allows closer observation of the present state of the posture and even the limiting tensions associated with it.

Satya: Truthfulness, Non-lying

Satya implies truthfulness, and that we speak being fully conscious of the powerful effects of what we say and how we say it (inwardly and outwardly; in speech, action and thought). Remember that actions have consequences, and speaking the truth may not be always desirable, for it could harm someone unnecessarily. Love is higher than truth, and “brutal honesty” is not truth. If love is behind how you use truth, you’ll be practicing both Satya and Ahimsa. Truth is not something that you learn, like knowledge, but something that is revealed, like wisdom.

Satya in Your Asana Practice:

Dishonesty in Asana may manifest in telling yourself you cannot do things that you actually can, or the other way around. During asana, for instance, be honest about the presence of aggression, the fluctuation of thought between past, present and future, the ability to bend your knee just a little bit more. Viewing honestly the current state of a pose sheds light into the nature of limiting tensions.

Asteya: Integrity, Non-stealing

The positive expression of Asteya is giving time, energy or things. Asteya may be clearer when it comes to the material world of objects, but it goes well beyond it. Jealousy would be a good example. Aligning ourselves with the principle of Asteya means that we accept the challenge of growing our own qualities and potentials from where we really are (Satya), living the life we want to live through our own merits. It is said that when you obtain what you want through honest means, you have no fear. If you attain what you want through dishonest means, you live with fear.

Asteya in Your Asana Practice:

Asteya can be applied to pranayama, for example, by keeping the in breath and out breath even: neither stealing from one nor the other. Since breath mirrors the mind, this will create a calm and balance inner state. But be also prepared to be flexible! If you are feeling too tired, you can make the in breath longer in order to drawn in more energy and refresh your mind; and you are feeling overexcited or nervous, you can make the out breath longer to relax your body and let go of tensions.

Brahmacharya: Moderation, Non-being Excessive

Traditionally, Brahmacharya meant celibacy in the monastic or ashram context. For those living in modern secular society, it can be viewed as the capacity to acknowledge the power of sexuality, and thereby to use it wisely. It also means moderation in all things as well as self-containment. The word Brahmacharya is composed of the root car, which means “to move” and the word brahma, which means “truth”. So this Yama can be understood as a movement towards the essential truth, or as responsible behaviour with respect to our goal of moving towards the truth, suggesting that we should form relationships that foster our understanding of the highest truths. In terms of sexuality, it means neither obsessing nor repressing, but making peace with your sensual cravings or any interests that pull you off-centre from your Source.

Brahmacharya in Your Asana Practice:

Consistently re-focussing our awareness on what’s happening on the mat allows observation of our energy levels so we administer it to complete the practice properly.

Aparigraha: Generosity, Non-possessiveness

Aparigraha can be understood as abstaining from accumulating more than we need. To have “stuff” is not an issue in itself, the problem is when we become attached to it. Aparigraha can then be defined as taking only what is necessary, and also as uprooting the tendency to reinforce who we are by what we own and do. Sometimes we try to satisfy spiritual starvation with distractions (relationships, sex, food, material goods, etc.). If we remove the distraction, we can connect more deeply with what is really happening inside us. That is also Aparigraha.

Aparigraha in Your Asana Practice:

Greed in asana could manifest as a desire for more strength or ability to perform complicated asanas, often judging ourselves for not being strong or stable or flexible enough. If generosity was applied here, noticing that we are growing in strength, stability or flexibility, the focus would be brought back to the path and allow a balanced progression along it.